by Ariel Penn

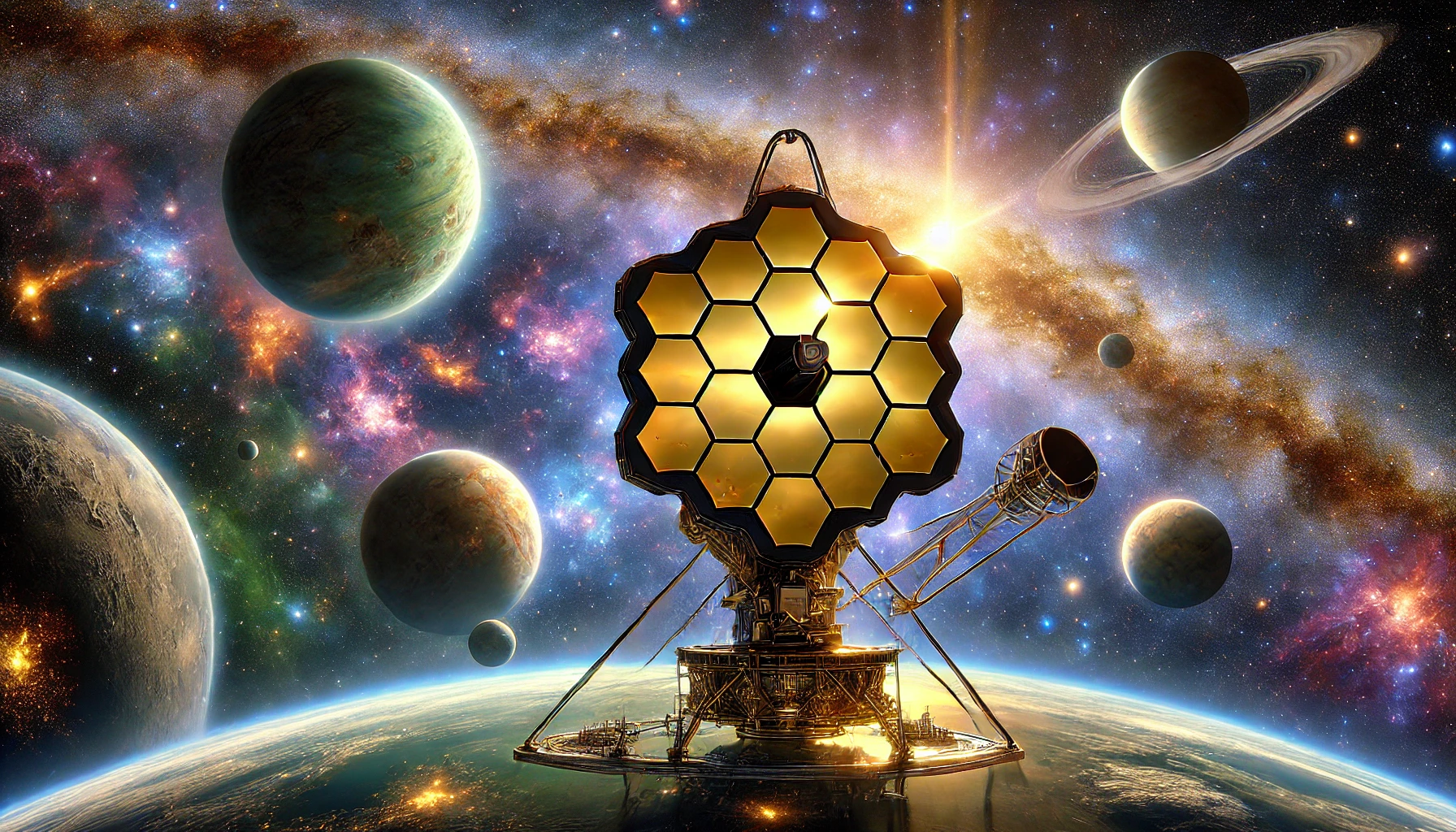

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to live on another planet? Thanks to NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, scientists are getting closer to learning whether some distant planets could be just right for life. Dr. Knicole Colón and Dr. Christopher Stark, two scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, recently shared the latest updates on how we study these strange new worlds—and why it’s not quite as simple as it sounds.

What Makes a World “Potentially Habitable”?

When scientists talk about a “potentially habitable” planet, they usually mean:

- It’s about the size of Earth (small and rocky).

- It orbits in the habitable zone of its star, which is the “Goldilocks” distance where the planet could be warm enough for liquid water to form on its surface.

So far, Webb has found roughly 30 planets that fit these basics. But just because a planet hangs out in the habitable zone doesn’t mean it actually has water—or any form of life. Right now, Earth is still the only place scientists know that’s both habitable and inhabited.

Different Stars, Different Habitable Zones

Stars come in different sizes and brightnesses, and this changes where the habitable zone falls. For instance:

- G-type stars (like our Sun) are medium in size and temperature.

- K dwarfs are smaller and cooler than our Sun.

- M dwarfs (also called red dwarfs) are the smallest and coolest of the bunch.

Because these stars are so different, each has its own habitable zone. In our solar system, the habitable zone starts just beyond Venus and comes close to encompassing Mars.

How Webb Checks for Atmospheres

Webb studies these planets by watching them transit their stars—that is, pass in front of the star from our point of view. During a transit, some of the star’s light filters through the planet’s atmosphere. By studying which wavelengths of light get absorbed, scientists can figure out what chemicals are floating around that planet—things like water vapor, carbon dioxide, or methane.

The Catch

For a small, rocky planet, the atmospheric signals are very faint (often less than 0.02% of the star’s light!). Spotting water vapor or signs of life (called biosignatures) is tougher still. That means it takes a lot of patience and a huge amount of observing time to gather enough information. Some planets might require dozens of transits before we can even guess if there’s life there.

Case Studies: LHS 1140 b, TRAPPIST-1 e, and Others

Only a few rocky planets in the habitable zone are good candidates for Webb to study. Two examples are LHS 1140 b and TRAPPIST-1 e.

- For LHS 1140 b, scientists recently calculated that spotting bio-signatures like ammonia, phosphine, or nitrous oxide might take anywhere from 10 to 50 transits. Since Webb can’t watch this planet all year round (the telescope’s schedule is complicated by the planet’s orbit and where it is in the sky), it could take years—or even a decade—to collect enough data. And if the planet is cloudy, we’d need even more transits!

- Another complication is that different gases can overlap in the signals they produce. It can be tough to tell the difference between, say, methane from life or methane from non-living processes. Sorting that out is like trying to pick out a single conversation in a noisy cafeteria.

Is That Water from the Planet… or the Star?

Sometimes, the planet’s star can trick us. Some stars (like red dwarfs) have cool spots that might hold water vapor. Recent Webb observations of GJ 486 b showed how a star could mimic the signals we’re hoping to find in a planet’s atmosphere. Figuring out whether water is from the planet or the star is an extra challenge—like trying to figure out which kid in a crowded classroom actually asked the question!

Meet the “Hycean” Worlds

Scientists also talk about “Hycean planets,” which might have a thin, hydrogen-rich atmosphere and a huge ocean of liquid water beneath it. One candidate for this type of world is K2-18 b. Webb spotted methane and carbon dioxide there, but no water signal yet. There’s a chance that K2-18 b could still be a watery world under a hydrogen atmosphere, but the evidence so far is mostly theoretical—meaning more observations are needed.

Researchers also caught a possible whiff of a chemical called dimethyl sulfide, which on Earth mostly comes from living organisms like plankton. But the signal was too weak to say for sure. Future Webb observations will help figure out if K2-18 b really does have these intriguing signs of life.

Looking Ahead

All these challenges add up to one important point: detecting life on an exoplanet isn’t going to be easy. Webb can detect some interesting gases on a handful of the most promising planets, especially those orbiting cooler stars. But a single biosignature isn’t enough to shout, “We’ve found alien life!” We’ll need:

- Multiple types of biosignature gases,

- Data from different telescopes and missions,

- Lots of computer modeling,

- And loads of time to make sure we’re not getting tricked by anything else (like starspots or overlapping signals).

Webb’s findings will also help pave the way for future missions, like NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and the eventual Habitable Worlds Observatory, which will be our first mission designed specifically to directly image (take pictures of!) Earth-like planets around Sun-like stars.

In other words, the hunt has only just begun. Webb is giving us a sneak peek at planets across the galaxy, helping us figure out if any might be just right for life. Who knows what we’ll discover in the years ahead? One thing’s for sure: with each new glimpse beyond our solar system, we’re inching closer to unlocking the mysteries of the universe—and that’s worth getting excited about!